In just the past few years, large machine learning models have made incredible strides. Today’s models are not only remarkably capable but also achieve impressive results across a range of applications, from software engineering and scientific research to content creation and data analysis. With the arrival of models like Kimi-K2.5 and GLM-5, the pace of progress shows no sign of slowing down. (Kimi-K2.5 has an impressive 1 trillion parameters, nearly twice as many as the DeepSeek V3 model family that was released just last year.) And as these models continue to grow in size and capability, so does the demand for memory, computing power, and energy.

One of the most effective ways teams are addressing these constraints is through low-bit inference, a set of techniques widely adopted across the industry that make AI models faster and cheaper to run by reducing how much memory and compute they need when serving real user requests. At Dropbox, products like Dropbox Dash rely on various models to deliver fast, reliable, and cost-effective AI-powered search and understanding across vast amounts of user content. Making this possible requires careful attention to model efficiency, hardware utilization, and latency constraints. And making this technology accessible to individuals and businesses means tackling new challenges around efficiency and resource use.

In this article, we’ll dive into the current landscape of low-bit compute for efficient inference. We’ll cover the different types of quantization, why and when they’re needed, and the key optimization challenges required to deploy advanced AI models in production.

The cost of running modern models

At Dropbox, almost all the models used in-house are attention-based architectures used for tasks like understanding text, images, videos, and audio—core capabilities behind Dash’s ability to search, summarize, and reason over large collections of user content. As these models grow in size and complexity, efficiently serving them in production becomes a central challenge for delivering responsive user experiences. In attention-based models, most of the compute comes from repeated matrix multiplications in two main parts of the model:

The first is the linear layers, which compute embeddings throughout the model. These include:

- The layers used within attention blocks, the components that determine how different parts of the input relate to one another

- MLP layers, which further process and refine those representations

- The model’s final output stage, where those representations are converted into a concrete result, such as a prediction or response.

The second is the attention mechanism itself, where the model evaluates relationships across the input to determine which information is most relevant, a step that significantly increases compute cost with longer context sizes.

On GPUs, these matrix multiplications are handled by specialized hardware. NVIDIA GPUs use Tensor Cores, while AMD GPUs use Matrix Cores. These dedicated processors are accessed through matrix multiply-accumulate (MMA) instructions and are designed specifically to accelerate matrix operations—the heavy-duty math that underpins large-scale linear algebra in neural networks—delivering substantial performance gains compared to executing the same work on general-purpose CUDA Cores.

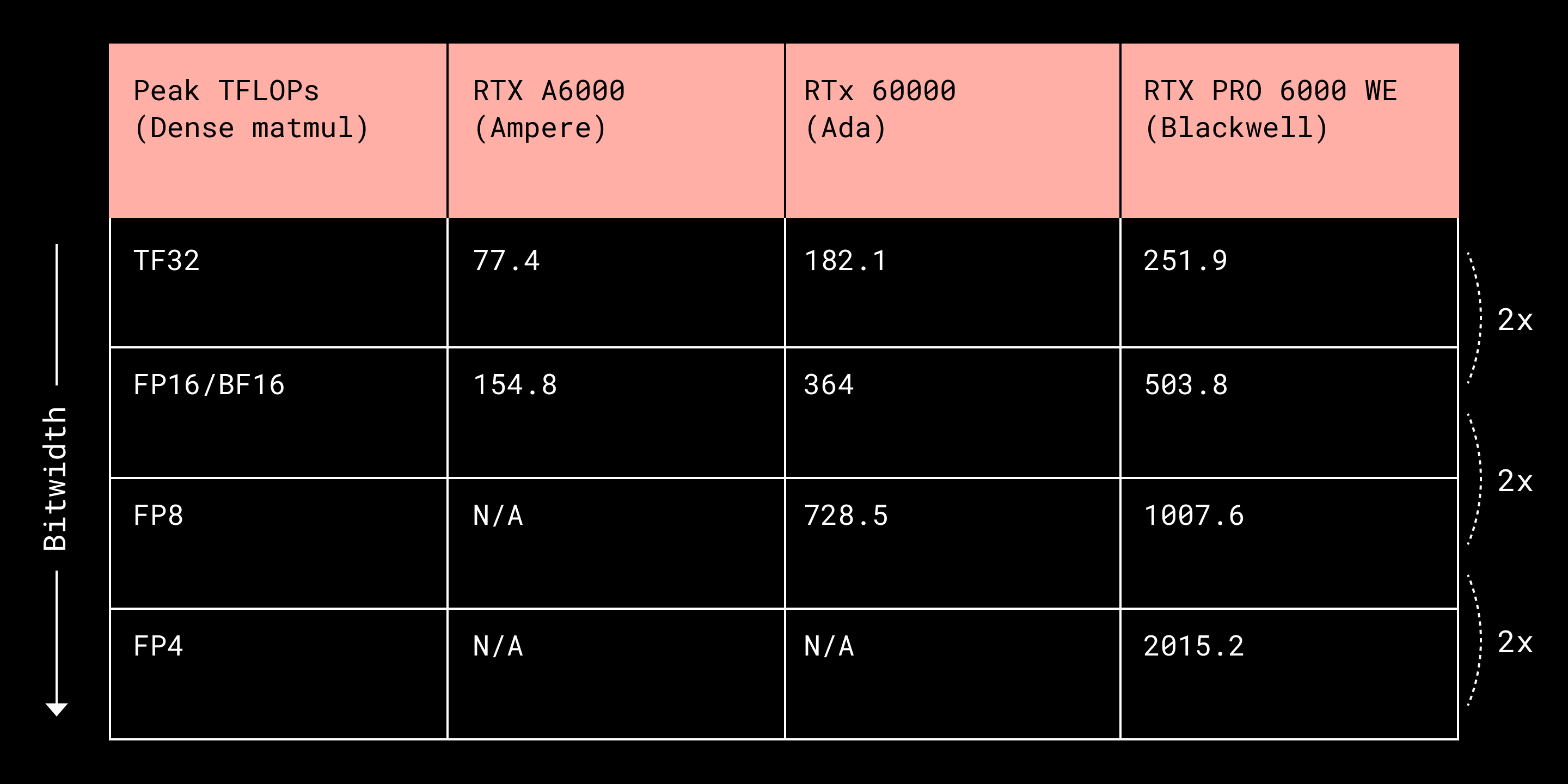

One notable property of these cores is their scaling behavior. As numerical precision is reduced, these cores can perform more matrix operations per second, typically resulting in higher FLOPS (floating point operations per second, or how much math the hardware can do in a given time). In practice, halving the precision often allows these cores to roughly double throughput. This scaling behavior plays a key role in improving both performance and efficiency when running large-scale AI workloads.

Fig. 1: Tensor Core dense matrix multiplication performance (FLOPs) across different NVIDIA RTX 6000 variants and data precisions

Lowering numerical precision is accomplished through quantization, a technique that reduces the number of bits used to represent numerical values. By quantizing tensors, for example, from 16-bit to 8-bit or 4-bit, the memory footprint is reduced because each element requires fewer bits. This is typically done by rescaling the data to fit within a smaller representable range. For instance, 8-bit quantization maps values to 256 bins, restricting each tensor element to one of these discrete levels while approximating the original floating-point values. Quantization to lower than 8 bits typically requires an additional process called bitpacking, where multiple low-bit elements are combined into a native data type such as uint8 or int32, since 4-bit formats are not natively supported.

Lowering precision not only improves speed and memory usage, but also improves energy efficiency, since lower-bit data requires less power for both memory transfer and computation. For instance, with FP4 support, Blackwell offers significant energy savings compared to the H100.

There have also been attempts to explore lower bits such as binary and ternary weights (restricting weights to two or three discrete levels), which would offer even more theoretical energy efficiency. However, this form of quantization isn’t well suited for modern GPUs because it can’t fully leverage Tensor/Matrix Cores. Although there have been experimental efforts to explore custom hardware or specialized accelerators tailored to such schemes, this approach hasn’t yet seen broad industry adoption as a result of limited ecosystem support and model quality concerns. In short, while lower precision can dramatically improve efficiency, real-world gains depend on how well those formats are supported by existing hardware and software ecosystems.

In the following section, we examine different quantization configurations and highlight their key trade-offs when deployed on modern GPUs.

Understanding quantization formats

Quantization is not a single technique, but a family of approaches that differ in how numerical values are represented, scaled, and executed on hardware. These design choices directly affect model accuracy, performance, and how efficiently modern GPUs can accelerate inference. As a result, quantization formats are closely tied to the capabilities and constraints of the underlying hardware.

In practice, these differences matter because Dropbox runs a diverse set of AI workloads—such as multimedia understanding—across multiple generations of hardware, each with distinct performance characteristics. Some workloads are highly latency sensitive, prioritizing fast per-request execution, while others are throughput oriented and optimized for processing large volumes of data efficiently. Quantization formats influence how well a model can adapt to these constraints, determining whether computation is bound by software overhead, memory bandwidth, or specialized hardware units like Tensor Cores. Framing quantization through this lens helps clarify why different formats unlock different tradeoffs across our stack, and why no single approach is optimal for every workload we deploy.

With the introduction of the MXFP microscaling format, which standardizes low-bit data types with native hardware support, quantization methods for large language models can be broadly grouped into two categories: pre-MXFP formats, which rely on explicit dequantization and software-managed scaling, and MXFP formats, which move these operations directly into Tensor Core hardware. The sections below walk through both approaches, highlighting how they differ in practice and why those differences matter for real-world inference workloads.

Pre-MXFP formats

Prior to the introduction of MXFP, quantization primarily relied on integer data types for sub-byte formats. Common configurations included A16W4 (16-bit activations, 4-bit weights) for weight quantization, and either integer or floating-point formats for activations, such as A8W8 (8-bit activations, 8-bit weights). In contrast, sub-byte weight quantization generally requires calibration or more advanced algorithms to maintain model quality. For example, A16W4 relies on techniques such as AWQ or HQQ—quantization methods designed to preserve model quality at low bit widths—while lower-bit formats like A16W3, A16W2, and BitNet require increasingly sophisticated training quantization methods to achieve acceptable accuracy.

When activations and weights use different data types, the typical approach is to explicitly dequantize the lower-bit tensors to match the higher-precision format before performing the matrix multiplication (MMA) operation. This strategy can improve performance in memory-bound scenarios, where reducing data movement is the primary concern. However, in compute-bound workloads, the additional dequantization step can offset these gains and even slow execution due to the extra arithmetic involved.

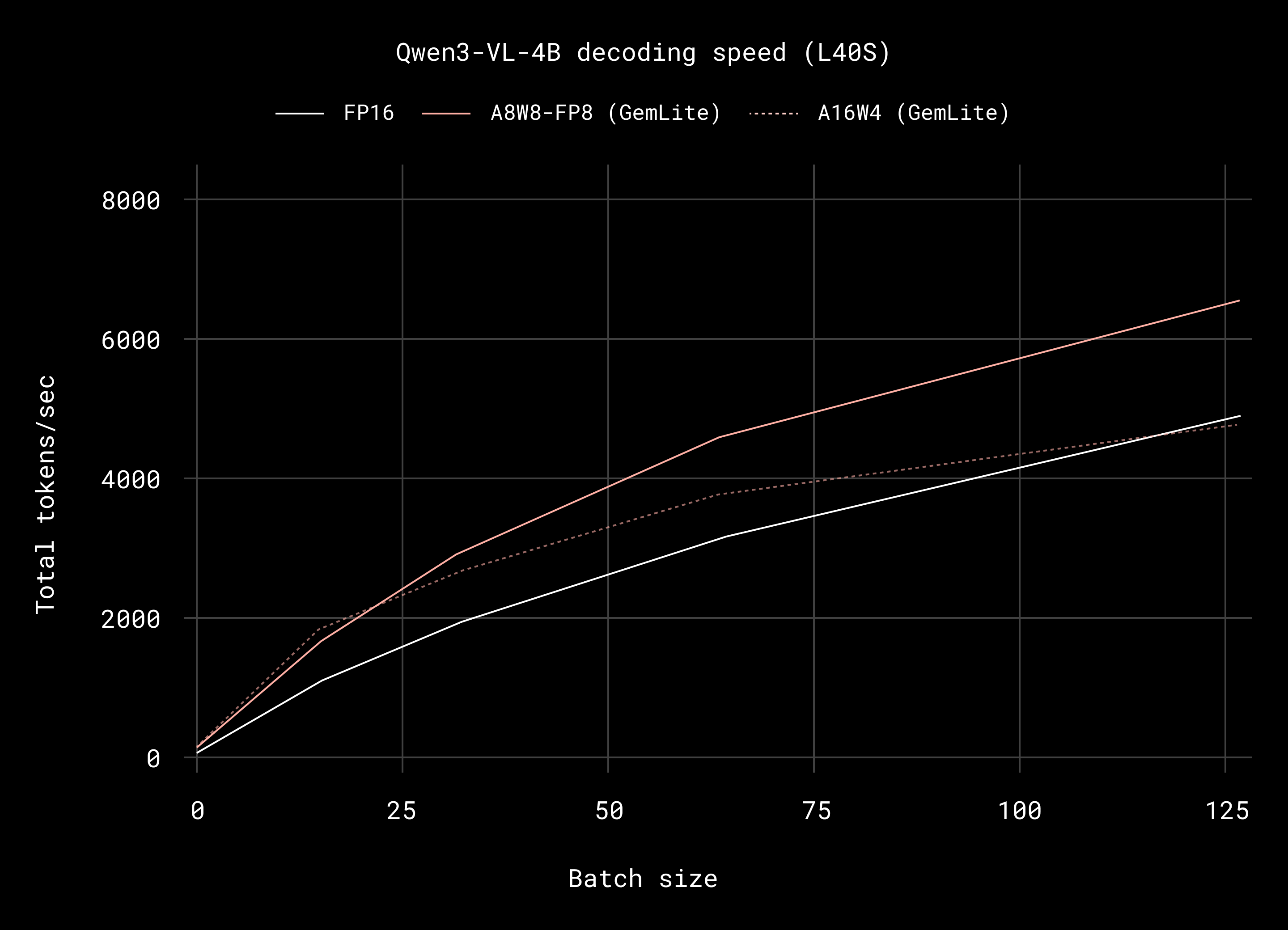

This trade-off is especially visible in weight-only quantization, which reduces data transfer but does not accelerate the extra computation required to run matrix multiplications. The choice between activation quantization (such as A8W8) and weight-only quantization (such as A16W4) ultimately depends on the characteristics of the inference workload. Weight-only quantization often performs better in local deployments with smaller batch sizes and reasoning-heavy tasks, where memory bandwidth is a limiting factor. In contrast, activation quantization tends to be more effective for large-context prefills and high-throughput serving scenarios, where compute becomes the dominant bottleneck.

Fig. 2: A8W8 vs. A16W4 decoding performance across various batch sizes. A8W8 tends to outperform A16W4 in more compute-bound scenarios. A16W4 tends to perform worse than 16-bit matrix multiplication due to the additional cost of explicit dequantization

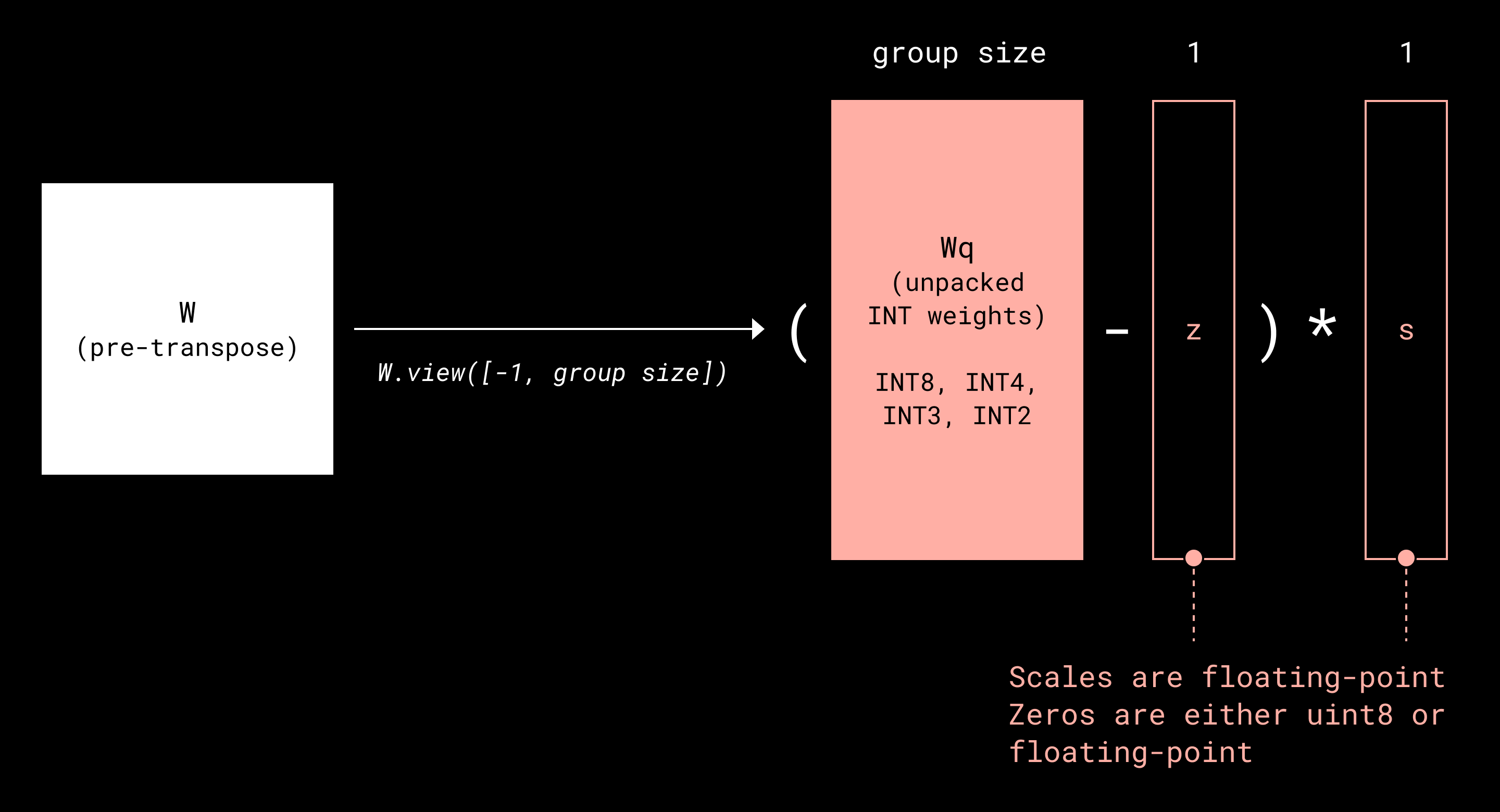

Popular methods such as AWQ and HQQ rely on linear quantization with grouping, a design that balances efficiency with accuracy. In symmetric linear quantization, dequantization is expressed as a simple scaling operation. A more flexible variant, asymmetric linear quantization, introduces an additional offset, allowing dequantization to be implemented as a fused multiply-add operation that maps efficiently to modern GPU hardware.

Grouping further improves accuracy by assigning shared parameters to small blocks of tensor elements rather than individual values. These groups typically consist of contiguous elements of size 32, 64, or 128. While simple, this approach substantially reduces quantization error at low-bit widths and has become a core component of most practical low-bit quantization schemes.

Fig. 3: Linear quantization overview where a matrix W is decomposed into Wq (low-bit tensor) and additional floating-point scales (s) and zero-points (z)

On the activation side, two 8-bit approaches are commonly used: channel-wise quantization and per-block quantization. Channel-wise quantization is straightforward and efficient, making it well suited for on-the-fly inference. The required rescaling can be applied directly after matrix multiplication, allowing for a highly efficient implementation on modern GPUs.

Per-block quantization, popularized by systems such as JetFire and DeepSeek V3, takes a more fine-grained approach. By dividing tensors into small tiles and assigning an independent scale to each block, this method limits the impact of outliers and reduces quantization error. It is particularly effective in quantization-aware training, where preserving pre-training accuracy is critical, while still delivering practical Tensor Core speedups.

Beyond linear quantization, several non-linear approaches, including QuiP# and GPTVQ, have explored alternative representations to push precision even lower. While these methods can achieve higher accuracy at very low-bit widths, they face practical challenges. Linear 4-bit quantization already delivers strong accuracy and can often be applied on the fly using techniques such as HQQ, avoiding expensive offline quantization passes. In addition, deploying non-linear formats efficiently requires custom fused kernels and deep integration into inference frameworks. Even then, low-bit weights must still be converted into a form compatible with Tensor Cores, making linear quantization both simpler and more practical on current GPU architectures.

Quantization techniques are also well-suited for optimizing the attention module. Methods such as Flash Attention 3 and Sage Attention use 8-bit quantization to accelerate attention-related matrix multiplications, improving throughput and memory efficiency with minimal impact on model accuracy.

MXFP formats

The MXFP microscaling format introduces a new standard for low-bit data types that fundamentally changes how quantized models run on modern GPUs. Unlike earlier formats, MXFP provides native hardware support for quantization, allowing Tensor Cores to operate directly on quantized activations, weights, and their associated scaling factors in a single fused operation. In contrast, pre-MXFP approaches required explicit dequantization steps before or after matrix-multiply-accumulate (MMA) operations, adding overhead and limiting achievable performance.

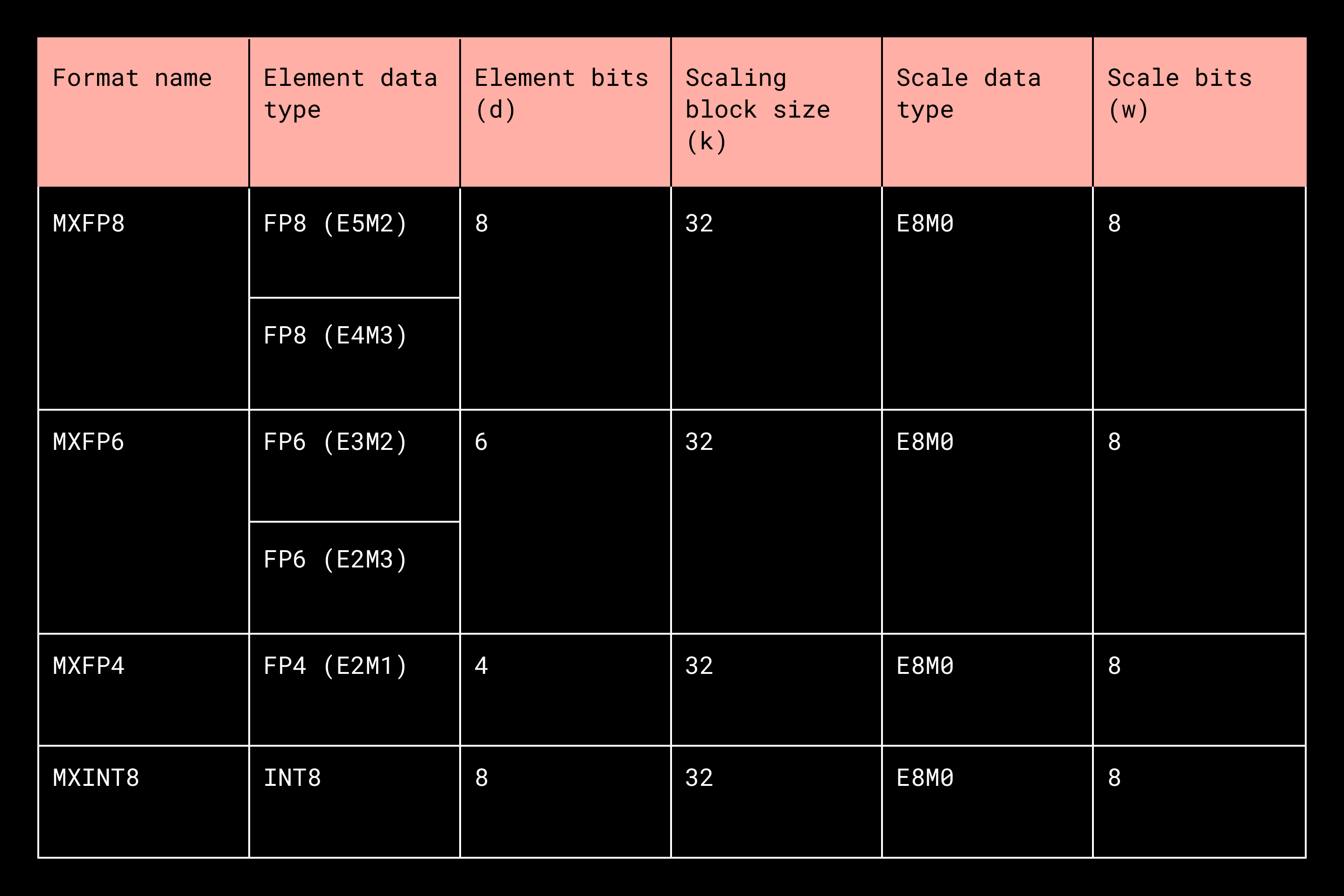

MXFP quantizes both activations and weights using a micro-scaling approach, similar in spirit to methods like AWQ and HQQ discussed earlier, but implemented directly in hardware. It uses symmetric quantization with a fixed block size of 32 and applies shared scaling factors stored in the E8M0 format. MXFP also supports mixed-precision MMA operations on some hardware, such as MXFP8 × MXFP4, giving practitioners flexibility to balance performance and accuracy. For example, activations can use MXFP8, MXFP6, or MXFP4 while the weights can remain in MXFP4. A breakdown of the MX types is demonstrated in the table below (source: Open Compute Project, OCP Microscaling Formats (MX) Specification, Version 1.0, Table 1).

Fig. 4: MX dtype breakdown

The E8M0 format for the scales represents positive powers of two in the range [2⁻¹²⁷, 2¹²⁷]. The scales are typically quantized as follows: scale = weight.amax(axis=1, keepdim=True) / max_val. As a result, scale values are effectively limited to values at or below 1, and extremely small magnitudes are rarely needed. In many cases, values as small as 2⁻¹⁵ are sufficient to capture near-zero weights. This observation suggests that scales could theoretically be represented with fewer bits than E8M0, although doing so would introduce additional complexity.

While E8M0 offers hardware-friendly implementation and flexibility, constraining scale values strictly to powers of two leads to a noticeable accuracy drop when using MXFP4. Fortunately, this loss can largely be mitigated through simple post-training adjustments, restoring most of the original model quality, as we demonstrated in our blog post.

To address remaining numerical limitations, NVIDIA introduced NVFP4 as an alternative to MXFP4. NVFP4 uses a smaller group size of 16 rather than 32 and employs E4M3 FP8 scaling factors, providing higher precision for scale representation. Because FP8 has a relatively large minimum representable value, a global per-tensor floating-point multiplier is applied to normalize the scaling range, achieving improved numerical stability.

Although MXFP4 and NVFP4 are standardized formats, their implementation depends on the GPU architecture. Different compute capabilities rely on different Tensor Core instructions. For example, sm_100 architectures use the tcgen05.mma instruction, while sm_120 architectures use mma.sync, both incorporating the block_scale modifier. As a result, kernels compiled for sm_100 are not portable to sm_120 due to these instruction-level differences. While most of the mainstream AI software stack remains focused on server-grade GPUs like the B200 and B300, there has been significant recent progress toward improving portability of low-bit workloads. Notably, Triton has introduced support for MXFP on sm_120 devices, enabling greater flexibility and cross-device compatibility for low-bit Triton kernels.

Looking forward

In this article, we explored several quantization techniques that are widely adopted across the industry to accelerate AI workloads. These approaches unlock substantial gains in efficiency and throughput, making it possible to deploy increasingly large and capable models within practical hardware, cost, and energy constraints.

At Dropbox, these considerations are central to how we build and operate products like Dash. Dash relies on large-scale models for experiences such as conversational AI, multimodal search, document understanding, and speech processing, all of which must meet strict latency, reliability, and cost requirements. To satisfy these constraints in production, we already employ a range of quantization strategies to optimize model deployment and fully utilize modern accelerators. The techniques discussed here reflect the kinds of trade-offs we evaluate when deciding how and where to run models across our infrastructure.

Despite the progress, important limitations remain. In real-world deployments, adoption of formats such as MXFP and NVFP is still evolving, and support for FP4 quantization remains incomplete across popular frameworks and model stacks. For example, many open-source runtimes don’t yet provide full support across different GPU architectures, and FP4 models are not yet widely available.

As hardware continues to evolve and the industry pushes toward lower-bit compute, these challenges will only become more pronounced. In our view, making low-bit inference viable for production systems like Dash will require tighter software design, more mature framework support, and new quantization techniques that preserve model quality at scale. We view this as an active area of exploration, one that will directly shape how we deliver fast, reliable, and efficient AI-powered experiences to Dropbox users in the years ahead.

~ ~ ~

If building innovative products, experiences, and infrastructure excites you, come build the future with us! Visit jobs.dropbox.com to see our open roles.

Dropbox Dash: The AI teammate that understands your work

Dropbox Dash: The AI teammate that understands your work