In 2018, Dropbox became the first major tech company to adopt high-density SMR (shingled magnetic recording) technology for our storage drives. By 2019, our SMR fleet size was around 25%. Today, a staggering 90% of our total HDD fleet size is now SMR capable, and we’ve continued to lead the industry in adoption with the deployment of two additional SMR hard drive models.

SMR technology has reduced the power requirements of our storage servers, lowered the cost of each exabyte, and enabled more efficient server rack designs. The work that we’ve done and the lessons we’ve learned have helped raise the bar for everyone in the industry using SMR drives.

It’s been an amazing journey, and we’re excited for what the future holds—from new recording techniques and server designs, to emerging software features and deeper collaboration with our vendors. Here’s how improvements in SMR technology over the last four years have been integral to the work we do.

More density

Dropbox has been on the cutting edge of improvements to disk recording techniques, platter count, and storage enclosure design—all of which, when combined, have enabled huge leaps in density across our fleet.

Our initial deployment of SMR drives enabled us to take advantage of a recording technique called shingling, where tracks of data overlap like the shingles on a roof, thus increasing the number of tracks per inch (TPI). When shingled, track width is no longer limited by the size of the write head, but the size of the read head, which can read a much narrower track. Shingling increases the capacity of SMR drives by about 20% over conventional perpendicular magnetic recording (PMR) drives.

More recent SMR drive models have brought further improvements in disk recording techniques—namely two-dimensional magnetic recording (TDMR), which introduces an additional reader per head. These two readers improve read accuracy by enhancing signal detection and canceling noise from inter-track interference. TDMR has made it it possible to write even narrower tracks of data, further increasing the areal density of our SMR drive’s platters.

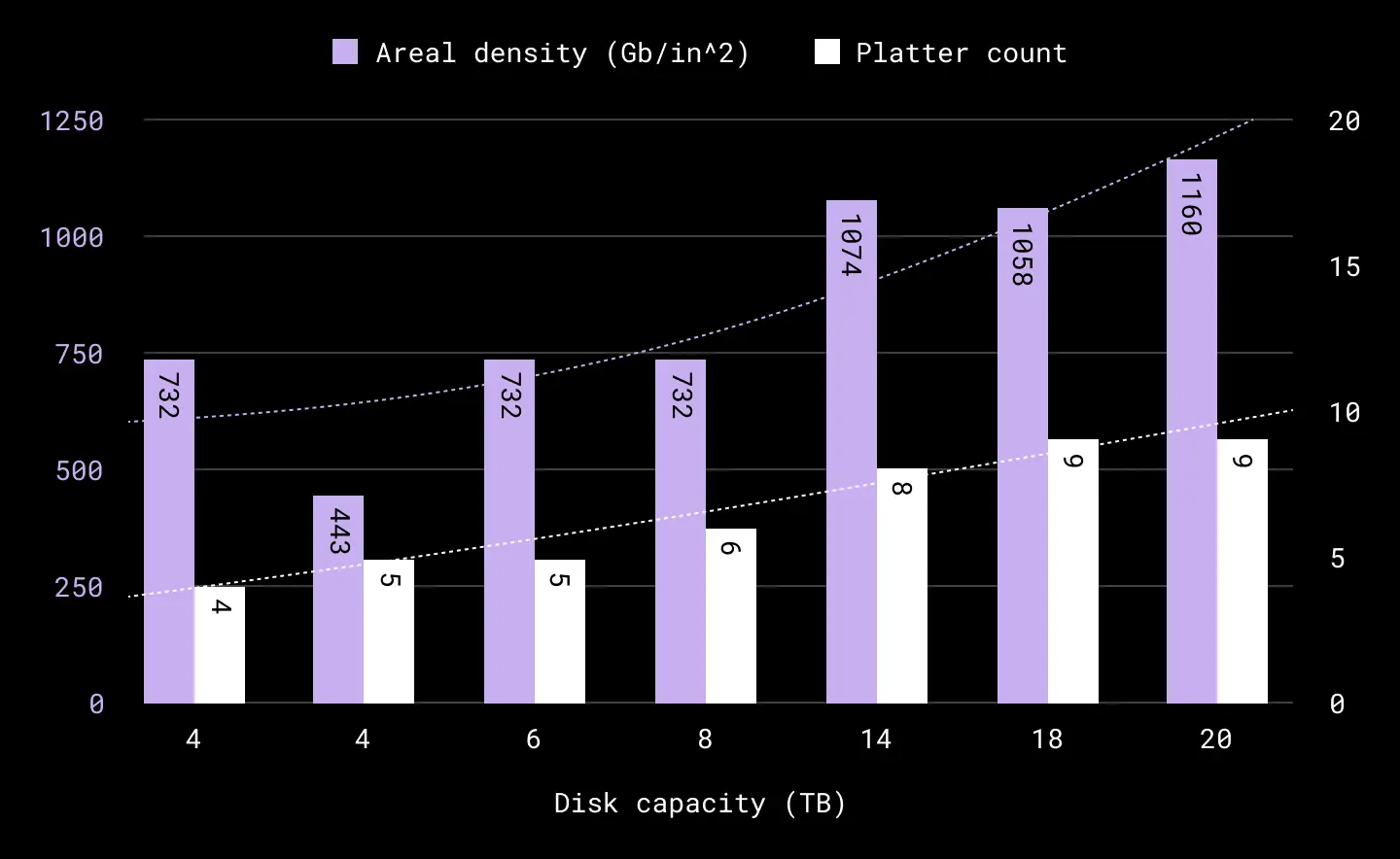

Platters have also been getting thinner, and the platter count in our disk drive enclosures has steadily increased. More platters mean we have more surface area to store our bits—yet another trend that continues to push our storage capacity gains. Our most recent drives boast nine platters and eighteen heads—more than double that of the first drives we ever deployed. It’s worth noting that the spacing between platters is now measured in nanometers, a testament to our vendors’ amazing advances in engineering at the nanometer scale.

Trends for both areal density and platter count for our deployments at Dropbox, from PMR to SMR. It is interesting to note that areal density improvements—expressed as bit-per-square inch—grew at a much faster rate from 14 TB ↔ 20 TB compared to 4 TB ↔ 8 TB. Areal density is currently tapering off at around the ~1 TB/in^2 band, double that of our first drive deployment

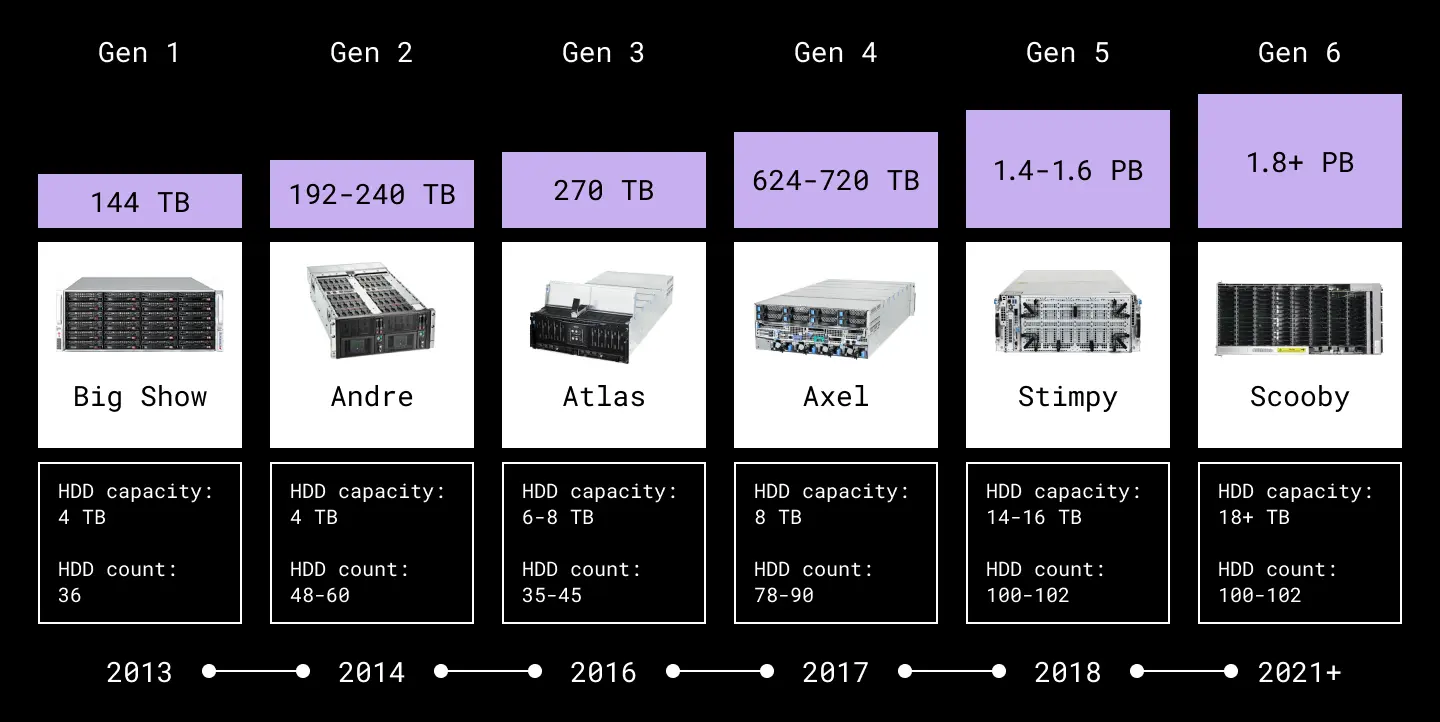

Finally, our storage designs have evolved since our first launch. One of the many criteria in our designs is enclosure count, or how many 3.5” HDDs we can physically fit into a server. The main tradeoff with increasing this count is that it becomes harder to cool the enclosure and stay under our HDD thermal window of 45°C. Nevertheless, we’ve managed to increase enclosure count by 2.8x since our first generation design, and have increased this a further 1.8x since we started deploying SMR drives—all while still adequately cooling our HDDs. Going forward, we don’t foresee major further increases in enclosure count, and plan to shift more focus to thermal and vibration efficiencies instead.

Note how we’ve increased the number of HDDs in our enclosures by 2.8x since our first generation design

Less power

The energy required to operate our hard drives is measured in power consumption per terabyte (TB/watt). Since our first 4 TB deployment, TB/watt has decreased by around 5-6x—largely because our SMR drives can cram more terabytes into the same physical and energy footprints as conventional PMR drives.

Our very first 14 TB SMR drive almost cut our power footprint in half for idle and random read workloads compared to its PMR predecessor. Our latest 18 TB and 20 TB drives show an amazing ~.30 watts per 1 TB in idle and ~.50 watts per 1 TB for random read workloads. Data from our vendors suggests this trend will continue, even as capacities increase.

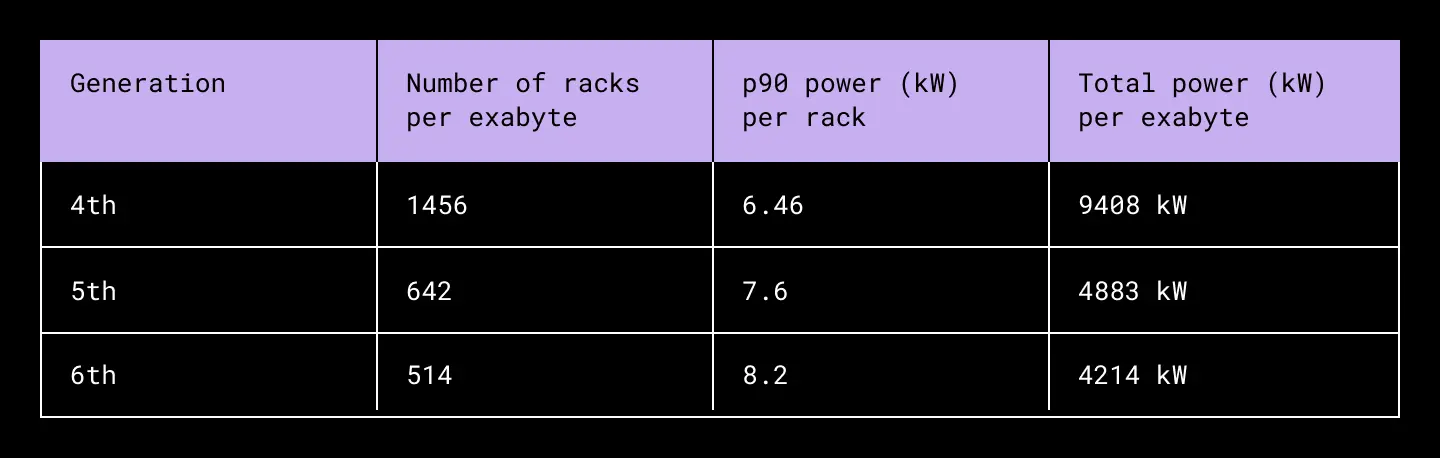

If we zoom out and look at the cost of serving an exabyte of data, the power savings become even more apparent. Our sixth generation storage server needs five fewer megawatts and just a third of the physical rack space to serve an exabyte of data compared to our fourth generation design. Ultimately, these power efficiencies mean less power is consumed by our data centers—an important part of meeting our sustainability goals.

Less money

Now that 90% of our fleet consists of SMR drives, we’re happy to report that the cost benefits we identified in our first year have remained the same. We continue to be able to store roughly 10-20% more data on an SMR drive than on a PMR drive of the same capacity at little to no cost difference. Over time, this means we’ve been able to provide the same capacity with fewer drives—and from a $/exabyte standpoint, our SMR leadership has helped to substantially drive down our storage infrastructure costs.

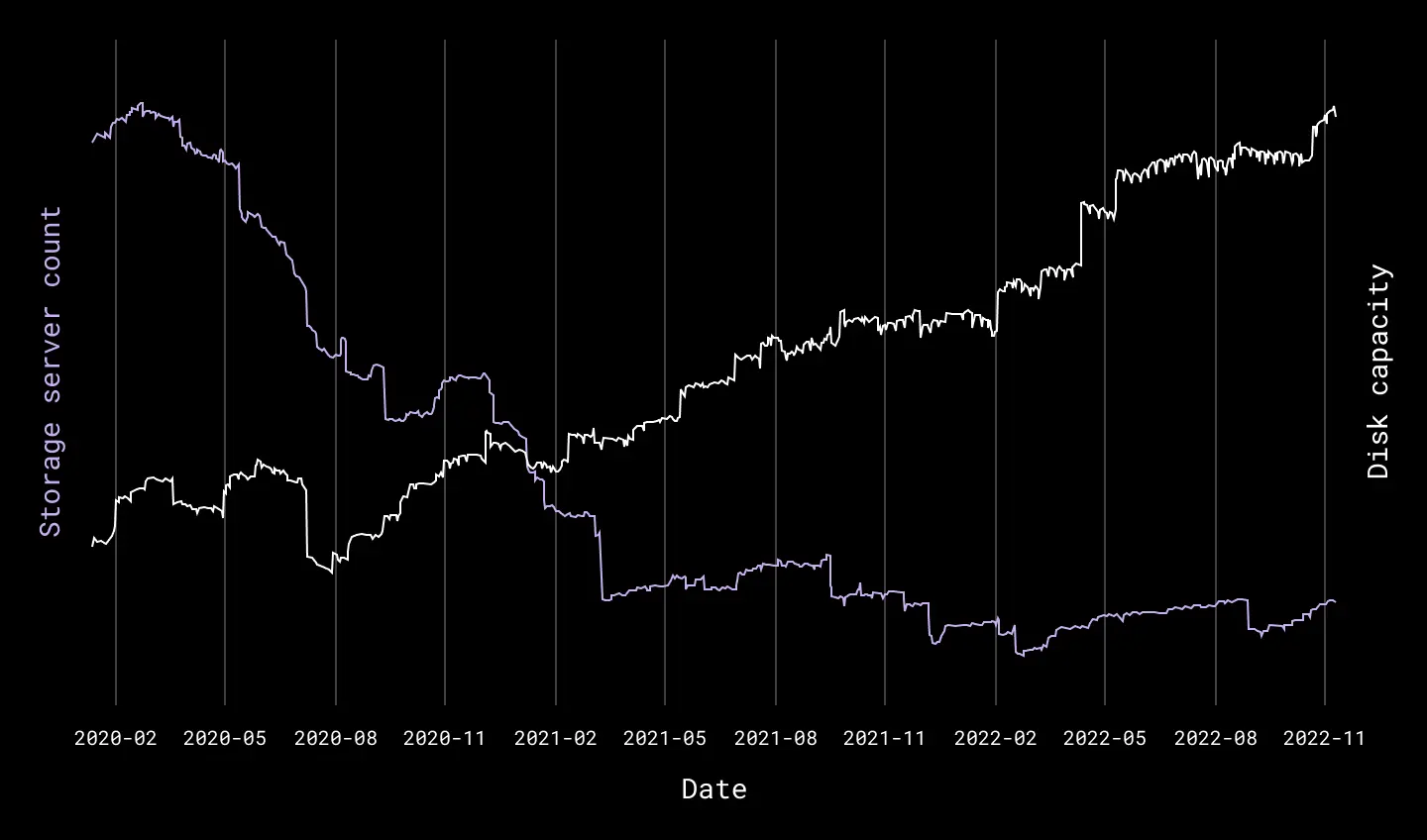

Another pleasant surprise is that, as our overall capacity has increased, the physical footprint of our storage has actually decreased! This was mostly due to our smaller capacity 4 TB, 6 TB, and 8 TB drives being decommissioned and replaced with higher density models; a single, high-density SMR drive could replace four or five 4 TB drives.

A smaller fleet takes less effort to manage, means fewer repairs, and requires less space and power in our data centers. The implications of this were obvious to everyone at the time of initial deployment—but it’s another thing to actually see those cost savings add up over time.

Overall storage capacity has grown while the number of hosts have decreased

Better software

As more companies adopt SMR drives, the software ecosystem supporting SMR has also matured. For our initial deployments, Dropbox used a custom disk format and the open source library libzbc to perform read/write operations on SMR drives without leveraging any filesystem. We are currently incorporating new advancements into our stack—such as support for zoned devices in the Linux kernel and advanced capabilities provided by libraries like libzbd—as they eliminate the need for custom disk formats. The libzbd library, for example, provides advantages such as asynchronous I/O capability, higher queue depth, priority-based I/O, compatibility with block trace tools, and reduced overhead in comparison to libzbc.

We are also still making improvements to our internal testing tool SMRtest, which generates synthetic workloads that mimic production. Some recent updates include support for libzbd, multi-threading, and 4k sector size support. It is also nice to see support for zoned block devices added to fio with version 3.9. We have been using a mix of these test suites with our ecosystem partners, suppliers, and vendors depending on the use case.

Deeper collaboration

Dropbox has one of the largest host-managed SMR fleet in the industry, and the close relationships we have with our HDD partners have been key to our continued success. The biggest improvement to our evaluation process since deploying our first SMR drives has been to more deeply integrate our partners into our large scale testing phase. During this phase, our vendors now run a mix of vendor and Dropbox workloads at scale with our exact storage hardware at their site. In addition we have developed an in-house simulator of Magic Pocket, which allows our hardware engineering team to gain even more fidelity signal earlier in our hardware evaluation.

This strategy accomplishes a few things:

- Bugs are easier to reproduce. This is because both our vendors and Dropbox are running on identical hardware, software, and firmware stacks, ruling out interoperability issues that don’t apply to us.

- Increased velocity. Having hardware physically close to the experts reduces the time to find the root cause of a problem and take corrective action. Imagine a scenario where an HDD engineer can walk over to Dropbox hardware and pull a SATA trace, develop a fix, test the patch, and iterate at their facilities at their own pace—without having to coordinate multiple meetings in different time zones or wait for access to physical hardware.

- Scale. Some bugs don’t appear until after you hit a certain scale or a significant number of drive hours have passed. During our at-scale testing we deploy around 5,000+ drives, which typically surpasses the scale that the vendors themselves test with.

- Earlier signal. Our in-house tool allows us to mimic production-like workloads in a safe testing environment, meaning we can catch any issues before new drive models are deployed to production.

The close relationships we have with our vendors enabled us to ship two new SMR deployments which have accumulated several billion drive hours in production. This strategy has not only benefited Dropbox; the feedback and findings we share with our vendors eventually make their way into publicly available hardware and software, benefitting the SMR ecosystem as a whole.

The future

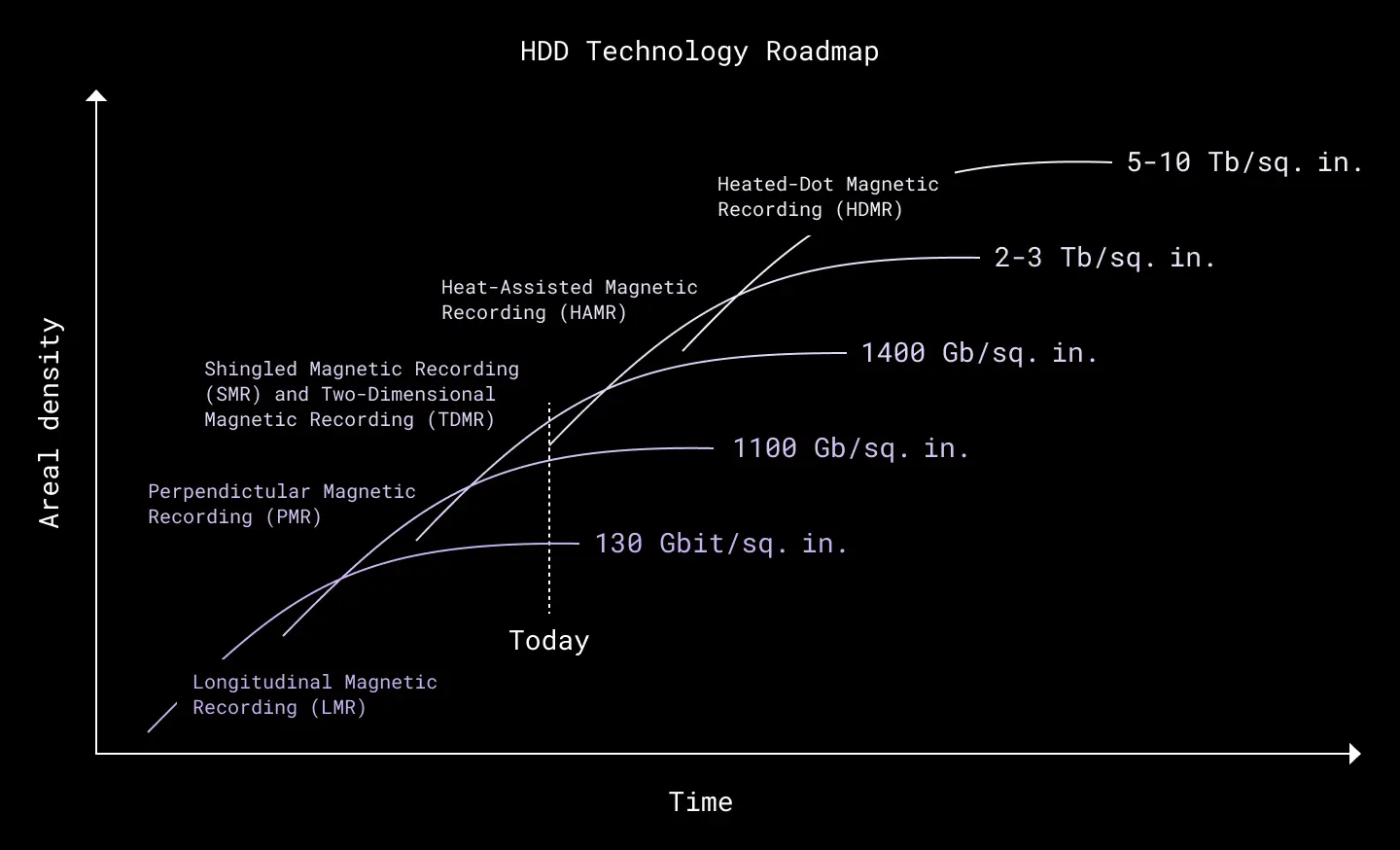

The Advanced Storage Research Consortium (ASRC) issues the technology roadmap for the HDD industry

In recent years, we’ve been riding a band of areal density—driven by SMR and TDMR technologies—that is finally tapering off. While there is still incremental progress within this band, such as increases in the number of platters and incremental areal density improvements, there is a new band quickly approaching.

Progressing to this higher band of areal density requires smaller media grains, higher media magnetic anisotropy—to protect against inadvertently switching the grain—and sufficient head field to switch the high anisotropy grains. Researchers call this the magnetic recording trilemma, but a new recording technique called heat-assisted magnetic recording (HAMR) offers a solution.

Whereas SMR increased density by overlapping tracks of data, HAMR goes further by reducing the size of the bits in each track. In a HAMR system, the head temporarily spot-heats the media to 450°C during recording. This operation, measured in nanoseconds, softens the new disk medium and produces smaller thermally stable grains which enable smaller bits—and, in turn, an increase in areal density. We expect this new band, driven by HAMR, will enable disk capacities of 50 TB and beyond.

Compared to SMR, HAMR will require a new read/write head design, new disk media (FePT material), new drive firmware, and a different manufacturing process. But from a Dropbox perspective, HAMR is transparent to the host and should look and operate like a normal HDD. We’ve also seen data from our partners that shows equivalent reliability and manufacturability to SMR.

Our sixth generation storage server contains ~100 drives per rack

In anticipation of this next jump in areal density, our focus has shifted from increasing the number of HDDs in our enclosures to minimizing the impact that physical vibrations can have on the I/O performance of higher density drives. While there was much more margin for vibrations in prior designs, that margin is now much less as HDD data tracks become smaller and spaced more closely together. It’s common to see high frequency vibrations cause head positioning errors, which can, in turn, cause performance degradation. Vibration can come from fans, the rotational forces and seek actions of nearby HDDs, even the HDD itself—or, when frustrated enough, a yelling engineer. 🙂

Our focus in the future will be to minimize HDD performance degradation from system vibrations by suppressing structural vibration of the system chassis and reducing fan noise. Putting more focus into this area will be critical as we onboard next generation HDDs, and it’s great to see some efforts already underway in the Open Compute Project (OCP) community. We are planning to leverage the OCP’s HDD Acoustical Surrogate—a new industry-standard specification for vibrational testing—in our seventh generation designs.

Finally, higher density HDDs have challenged us to rethink where other bottlenecks lay in our infrastructure. For example, in order for our seventh generation server to theoretically support more than 6 PB in a single enclosure, we had to re-architect our network so we can drain and repair data at an acceptable rate. We also anticipate dual-actuator drives may eventually be necessary in order to meet our IOPs/TB requirements. Density increases can only go so far if there is still just one channel for I/O, but two channels will effectively double the IOPs our drives can sustain.

There are amazing advancements happening in the HDD technology space, ranging from nanometer track widths, recording heads flying only about a nanometer above the surface of a disk, platter material advancements, and new recording techniques such as HAMR. All these advancements provide a path to 100 TB HDDs. As exciting as the last four years with SMR have been, we’re even more excited for the road ahead.

If building innovative products, experiences, and infrastructure excites you, come build the future with us! Visit dropbox.com/jobs to see our open roles, and follow @LifeInsideDropbox on Instagram and Facebook to see what it's like to create a more enlightened way of working.

Acknowledgements: Facundo Agriel, Refugio Fernandez, Jesse Lee, Jared Mednick, Vishal Jose Mannanal, and Sandeep Ummadi also contributed to this article.

Dropbox Dash: The AI teammate that understands your work

Dropbox Dash: The AI teammate that understands your work